One of my favorite patient bloggers has a great post up today. Kairol Rosenthal at Everything Changes shares important things about what patients can do to help prevent medical error. Check out How Do You Prevent Errors in Your Care?

Campaigns that help patients become more active, more visible in their care are on the rise. The Joint Commission has one I like: Speak Up. The focus of campaigns like these--rightly, I think--is on behaviors patients and caregivers should engage in. But it's interesting to know the science behind the recommendations.

Patients are the last line of defense in a complex system of care. Ideally, errors are prevented (through strong system design and rigorous adherence to the processes designed to avert human error). But the next-best thing to preventing an error is to detect it and mitigate negative consequences before the error reaches and harms a patient. This is why the patient's (or advocate's) voice is so important. They are the last line of defense that can detect an error that's been set in motion. Knowing what to expect helps people recognize when things are not going as expected.

For example, asking "Did you wash your hands?" helps avert a common error of omission set in motion close to the patient. Errors arising close to the point of care are particularly hard to detect. (They stand in contrast to things like a physicians' prescribing error which--while potentially serious--routinely undergoes scrutiny by pharmacists and, in a hospital setting, nurses.) The likelihood of detecting and correcting an upstream error (like a wrong dose or wrong drug prescribing error) is good. The likelihood of detecting a downstream error (like failure to perform hand hygiene) is not.

Many clinicians are working to change cultural norms in their workplaces, things that discourage patients and professionals from speaking up when they have a concern about how care is unfolding. It's a viable strategy that helps cure a healthcare epidemic.

Kairol thinks they should be wearing a ribbon.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Enough! Hidden Hazards that Impair Safety

This morning my husband, my son, an exchange student and his host brother are holed up in what my mom would call a "no tell mo-tel" 30 miles south of snowy Nashville where I am waiting to greet them with tickets to tonight's Thrashers-Predators game. The boys gave up trying to complete the drive from Atlanta last evening when my husband, who grew up in Canada, said, "Enough." And not a lot more.

Unpredictable things that derail what we intend to do are annoying, and they can be dangerous. Like icy patches hidden under the snow, they're often hidden. Hazards are on my mind today.

On a larger scale, I've been reflecting about hidden places where safety gets derailed ever since a link to an article in the UK hit my Tweet stream last week. The headline and the original tweet used precious characters to say this: "Nurses who overdosed two Heartlands Hospital cancer patients escape punishment by professional body." The re-tweeted version that came to me included these words: "Sometimes sorry is not enough."

Based on the published account of these errors, the tragic events that resulted in the deaths of two patients did not happen because the nurses and physician intended to harm them. Rather, the processes they used to provide care on a regular basis failed when they were subjected to a drug's hidden hazard: Safe dosing of the drug involved, amphotericin, depends upon whether the specific product on hand is in a conventional or liposomal formulation.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices defines a series of routine checks and balances that should be in place in clinical settings where amphotericin is used. Differentiating--calling out in a way that is obvious and unmistakable to all clinicians who prescribe, dispense, and administer drugs with liposomal formulations--is one of the strategies necessary to prevent these errors. It's also worth noting that liposomal formulations of drugs are part of a group designated as "High Alert Medications" so-called because they are highly likely to cause grave harm when used in error.

The process the clinicians used the day two people in the UK died failed because it was insufficient to prevent or detect a potentially lethal error that was set in motion. The nurses told the professional board that they were "very sorry," words that seem to have fueled the grief of the families and caused some in the global community to judge them, too.

"I'm sorry," no matter how sincerely felt or expressed, does not restore the dead to the living. That is not the purpose of expressing remorse nor for accepting an apology. The survivors of a terrible tragedy caused by medical error must be supported in how they choose to proceed, dealing with the unwelcome life-altering changes such events hoist upon them. Survivors must be free to accept or not accept expressions of regret (although many find sincere apologies by individual clinicians and organizational leaders lessen their burdens).

But how we treat the people at the "sharp end" of a tragic system failure is ultimately a measure of safety culture. And it's a place where where good people (including many patient safety experts and healthcare professionals) slip on a hidden hazard. Saying that the nurses involved in this error "escape punishment" suggests they deserve punishment. And "sometimes sorry is not enough" leaves me scratching my head. What would be enough?

Postscript: You can access a recording of the IHI webcast mentioned above by clicking this [Link].

Unpredictable things that derail what we intend to do are annoying, and they can be dangerous. Like icy patches hidden under the snow, they're often hidden. Hazards are on my mind today.

On a larger scale, I've been reflecting about hidden places where safety gets derailed ever since a link to an article in the UK hit my Tweet stream last week. The headline and the original tweet used precious characters to say this: "Nurses who overdosed two Heartlands Hospital cancer patients escape punishment by professional body." The re-tweeted version that came to me included these words: "Sometimes sorry is not enough."

Based on the published account of these errors, the tragic events that resulted in the deaths of two patients did not happen because the nurses and physician intended to harm them. Rather, the processes they used to provide care on a regular basis failed when they were subjected to a drug's hidden hazard: Safe dosing of the drug involved, amphotericin, depends upon whether the specific product on hand is in a conventional or liposomal formulation.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices defines a series of routine checks and balances that should be in place in clinical settings where amphotericin is used. Differentiating--calling out in a way that is obvious and unmistakable to all clinicians who prescribe, dispense, and administer drugs with liposomal formulations--is one of the strategies necessary to prevent these errors. It's also worth noting that liposomal formulations of drugs are part of a group designated as "High Alert Medications" so-called because they are highly likely to cause grave harm when used in error.

The process the clinicians used the day two people in the UK died failed because it was insufficient to prevent or detect a potentially lethal error that was set in motion. The nurses told the professional board that they were "very sorry," words that seem to have fueled the grief of the families and caused some in the global community to judge them, too.

"I'm sorry," no matter how sincerely felt or expressed, does not restore the dead to the living. That is not the purpose of expressing remorse nor for accepting an apology. The survivors of a terrible tragedy caused by medical error must be supported in how they choose to proceed, dealing with the unwelcome life-altering changes such events hoist upon them. Survivors must be free to accept or not accept expressions of regret (although many find sincere apologies by individual clinicians and organizational leaders lessen their burdens).

But how we treat the people at the "sharp end" of a tragic system failure is ultimately a measure of safety culture. And it's a place where where good people (including many patient safety experts and healthcare professionals) slip on a hidden hazard. Saying that the nurses involved in this error "escape punishment" suggests they deserve punishment. And "sometimes sorry is not enough" leaves me scratching my head. What would be enough?

- An Ohio pharmacist is prosecuted, convicted, and jailed for criminal conduct following the death of a toddler who received a toxic chemotherapy infusion: Jail Time for a Medication Error – Lessons Learned from a Pharmacy Compounding Error. Is this enough?

- A midwife in the UK hangs herself, believing she is blamed for the death of an infant that followed a failed hand-off of key clinical data. The details appear in Midwife hanged herself thinking she was to blame for baby's death. Enough?

- A new resident physician commits suicide following a medical error. Expectations of perfection and what happens to people when systems are not strong enough to overcome human error are shared in Words fail, a moving tribute written by her colleague. Enough!

Postscript: You can access a recording of the IHI webcast mentioned above by clicking this [Link].

Monday, January 18, 2010

Not perfect

In the past few weeks, I've managed to lose my keys, my iPhone, and my way, predictable lapses known to occur when a person doesn't sleep or shower in the same place enough. So error, and how to mitigate predictable errror, had been on my mind.

To that end, I now possess 3 identical, well-parsed travel kits, one for home, one for my home away from home, and one for my gym bag. Standardize. Simplify. Before clicking "send," I ask for a second set of eyes on high-stakes transactions (like flight bookings). Independent double checks. Redundancies.

I know what reduces the chances that simple human error will occur or cause major set-backs in many processes. Last week, I was busy putting this knowledge to work for myself.

So it seemed like an odd time for counter-intuitive messages--things that show the benefit of imperfection--to crop up. But on Friday morning, I found myself captivated by a story about a mistake. (You can listen to this recollection, made more special because events weren't carried out as planned, in Story Corps' "When the tooth fairy overbooks, helpers step in," a daughter's precious memory of a father's slip.) And today I found Kent Bottles' interesting piece about why failure is important, which called upon a classic article "Teaching Smart People to Learn." (There's a link to the pdf in Kent's post.)

Trying to find the silver lining in the mistake cloud reminds me of a two quotes I used to keep on the bulletin board above my desk: Experience is what you do get when you didn't get what you wanted and Experience helps you recognize when you've made the same mistake twice.

Bon voyage! Safe travels!

To that end, I now possess 3 identical, well-parsed travel kits, one for home, one for my home away from home, and one for my gym bag. Standardize. Simplify. Before clicking "send," I ask for a second set of eyes on high-stakes transactions (like flight bookings). Independent double checks. Redundancies.

I know what reduces the chances that simple human error will occur or cause major set-backs in many processes. Last week, I was busy putting this knowledge to work for myself.

So it seemed like an odd time for counter-intuitive messages--things that show the benefit of imperfection--to crop up. But on Friday morning, I found myself captivated by a story about a mistake. (You can listen to this recollection, made more special because events weren't carried out as planned, in Story Corps' "When the tooth fairy overbooks, helpers step in," a daughter's precious memory of a father's slip.) And today I found Kent Bottles' interesting piece about why failure is important, which called upon a classic article "Teaching Smart People to Learn." (There's a link to the pdf in Kent's post.)

Trying to find the silver lining in the mistake cloud reminds me of a two quotes I used to keep on the bulletin board above my desk: Experience is what you do get when you didn't get what you wanted and Experience helps you recognize when you've made the same mistake twice.

Bon voyage! Safe travels!

Labels:

cognitive psychology,

human error,

Kent Bottles,

learning

Sunday, January 17, 2010

AHRQ's PS Net: Spiking the Kool-Aid with Truth Serum

Florence dot com has been on holiday. As I reflect on the hiatus, it's helpful to remember that the real Florence spent the final twenty years of her life in bed. (That's not what I've been doing, but it's information that helps establish expectations.) At the outset of this renewal, there are a few things about patient safety worth reiterating.

Few people are really "new" to patient safety. You become seasoned--recognizing what's gone right and what has or may have gone wrong--as soon as you begin to give or receive healthcare. Patient safety, simply put, is the science of preventing people from being harmed as a result of their need to seek care and how care is provided.

If you're a seasoned healthcare provider but new to the term "patient safety" or uncertain how it captures work you may be familiar with, I recommend viewing the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Patient Safety Network (AHRQ PS Net) site. It's a place where initiatives and approaches--some very familiar to bedside clinicians--are organized and categorized according to "where stuff happens," "how stuff happens," "why stuff happens," and "how to prevent stuff from happening." You get the point.

The site may sound academic, but it's not. Behind the taxonomy and useful glossary are a lot of easy-reads. Web M&M presentations, for example, rival prime time drama. (Just imagine the Kool-Aid in the screenwriter's room at House being spiked with truth serum.)

I hope you'll enjoy the (mostly) real-time dialogue about patient safety (and other things that capture my attention or imagination for a moment or two) this year!

Few people are really "new" to patient safety. You become seasoned--recognizing what's gone right and what has or may have gone wrong--as soon as you begin to give or receive healthcare. Patient safety, simply put, is the science of preventing people from being harmed as a result of their need to seek care and how care is provided.

If you're a seasoned healthcare provider but new to the term "patient safety" or uncertain how it captures work you may be familiar with, I recommend viewing the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Patient Safety Network (AHRQ PS Net) site. It's a place where initiatives and approaches--some very familiar to bedside clinicians--are organized and categorized according to "where stuff happens," "how stuff happens," "why stuff happens," and "how to prevent stuff from happening." You get the point.

The site may sound academic, but it's not. Behind the taxonomy and useful glossary are a lot of easy-reads. Web M&M presentations, for example, rival prime time drama. (Just imagine the Kool-Aid in the screenwriter's room at House being spiked with truth serum.)

I hope you'll enjoy the (mostly) real-time dialogue about patient safety (and other things that capture my attention or imagination for a moment or two) this year!

Friday, December 18, 2009

A Blue Christmas

The message inside the card reads, "Wishing you Christmas peace."

The message inside the card reads, "Wishing you Christmas peace."Some things just don't make sense.

Elvis-as-messiah is one of them. And why a pharmacist will spend Christmas behind bars this year for an on-the-job error is another.

You can read more about Eric Cropp and the circumstances behind the tragic death of a toddler here.

You can read more about Eric Cropp and the circumstances behind the tragic death of a toddler here.

Eric's address in the Cuyahoga County, Ohio jail appears at the bottom of the linked article. I'll be sending him one of the Elvis Christmas cards. There are 17 others in the box. I'll be happy to send one on your behalf, too.

Labels:

culture of safety,

Just Culture,

medication error,

punitive

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

These are a few of my favorite things.....

That's what Julie Andrews sang in the Sound of Music.

But I found them set to a different tune in a patient safety video created by nurse leaders who are DNP candidates. Thanks to Marie Duffy, Nancy Ramos, Cynthia Robotti, Rosita Rodriguez, and Sheryl Slonim for producing this excellent resource!

But I found them set to a different tune in a patient safety video created by nurse leaders who are DNP candidates. Thanks to Marie Duffy, Nancy Ramos, Cynthia Robotti, Rosita Rodriguez, and Sheryl Slonim for producing this excellent resource!

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

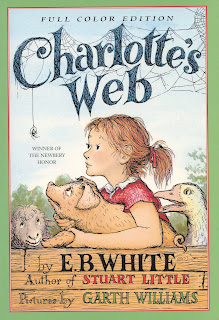

Grand Rounds at Charlotte's Web

Welcome to this holiday edition of Grand Rounds! It's the time of year when friends and family gather, when stories are told and memories are made. But the winter weather and short days here in the northern hemisphere seem to prompt brevity in our everyday comings and goings. It seems like the right time to combine storytelling and brevity and channel Charlotte, one of the most masterful storytellers I met during a childhood spent with my nose in a book.

In keeping with Charlotte's knack for saying what she meant and meaning what she said succinctly, I've categorized this week's submissions using six words that describe quality healthcare. (They're borrowed--in ways I suspect would make Templeton the Rat proud--from the Institute of Medicine's report Crossing the Quality Chasm.) This week participants were asked to submit one word describing the inspiration or take-away lesson for their post, and you'll find their words woven into today's Grand Rounds.

I hope you enjoy the tale. And do take the opportunity this holiday season to revisit Charlotte's Web. Better yet, share it with the next generation. As we seek solutions to the vexing issues healthcare bloggers wrote about for this edition, we'll be needing new words, spun by young people whose imaginations are ignited.

Last week The Blog of the Interdisciplinary Nursing Quality Research Initiative completed an ambitious commemorative series marking the 10th anniversary of To Err is Human. Since Florence dot com is, first and foremost, a real-time patient safety primer, I'm going to carefully letter my chosen word here: LEARN. And tell you to click on this link to access INQRI's lovely collection of stories, recollections, and sage advice.

Dr. Rich gets to the meat of the matter in Let Us Shun The Obese this Holiday Season. Dr. Rich's heart of darkness post (key word: demonization) could have fit nicely in many dimensions of care, patient-centered and effective sprung to mind. But his astute observation that obesity is often rooted in genetics makes it fit best here.

In The Users' Guide to the Health Reform Galaxy, Bruce Siegel stays on message with his word: equity. But read this post to learn why an insider believes minority groups could lose ground if health reform is not "done right." Louise from the Colorado Health Insurance Insider says the word is flaws and writes Why Health Care Reform is Important.

Amy Romano, CNM gets a blue ribbon in this category for maximin, a word I didn't know and one that would surely delight Charlotte. Amy wisely included a vintage PubMed link explaining her word, and she articulates her position in What SUVs Can Teach Us About Maternity Care. Paul Auerbach discusses The Canadian C-Spine Rule, with a take-away word of algorithm. Allergy Notes offers up "allergy" as an index word for the post describing the difference between food sensitization and food allergy.

Rounding out this dimension of quality healthcare are those who prompt us to pay attention to the quality and accessibility of high end data. Eve Harris offers transparency as the take-away lesson in Asking Dr. Science. Walter Jessen at Medpedia, an innovative 2.0 health information community, uses "reliable" to describe Medpedia Now Includes News & Analysis, Alerts, Q&A. And over at Clinical Cases and Images - Blog, we're reminded that it's also helpful to think. And rewarded with a thoughtful post, Medical Textbooks and Atlases Searchable on Google Books.

The ACP Internist offers Doctors, Ditch the Tie and Coat, an interesting piece about appearance (how patients' perceptions of providers are shaped by both culture and the providers' choice of attire). I found another new Charlotte-worthy word reading this post: zoris. (Check out the post to learn what it means if it's new to you, too.)

Laurie Edwards says the relativity factor is confounding when people with chronic diseases go about Learning to be a Primary Care Patient. Amy Tenderich winds up in the middle here, too, a welcome place according to her Wayback Wednesday post Oh, Glorious Middle. And Rachel's simply titled post is For Now. But the word she sent along, patience, may say even more about what patient-centered care really entails.

Jacqueline at Laika's MedLibLog captures the arachnoid spirit, giving her post a one word title: empathy. The post shows how much we long for care that considers more about who we are than our "chief complaint" often reveals. If Jacqueline had been in the mood to spin longer, she could have called this post, "What comes around, goes around!"

Developmentally appropriate care may mean calling on the healing power of friendship, something Nancy Brown points out in Helping Friends Who are Stressed and Depressed. In another part of the village, Barbara Kivowitz cautions that assumptions are not always helpful in Seven Myths about Couples and Illness. And Will Meek says the word is forgiveness and writes about it in How to Forgive.

One of the things I like best about the IOM's six dimensions of care is this: stakeholders don't always wind up tangled in their own little bitty egg sacs. Lock Up Doc offers the word transparency to explain her position on Should Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder Be Told Their Diagnosis? (It's a stance that also earns her a place in the coveted "patient-centered" category.) Curiosity earns The Happy Hospitalist a place here, too. (And his post Gynecological Exams: Best Done By Male or Female Gynecologists earns another label: funny.)

Dr Charles gives a nod to resilience in his post Hypochondriachal Heroism. And child psychiatrist An Ang Zhang explains something that makes healthcare delivery a challenge: Lying people. She says more in The Smartest Lie: Lord Winston; Super Doctors & The Dark Side. But At How to Cope with Pain, the word is contest! Visit for a holiday-inspired change of pace and see what's cooking! (Spoiler alert: It's not pork.)

Kim, a future nursing student, writes revisiting my hospital stay. Although she sent patience along as her take-away, I've chosen to place her post here because omissions count in quality measures. Rats!

Harry Stern at InsureBlog is worrying about supply and demand, too. His post, More (Un?)Intended Consequence, projects doctor shortages and backs up rather glum predictions with data from the Association of American Medical Colleges. ACP Hospitalist echoes the concern, with a call-to-action word: need. The post is New York survey shows dire need for hospitalists, internists. I'll take this opportunity to weave in a bit of Cavatican-style cheer: mid-levels.

At Shoot Up or Put Up, Tim's NHS pharmacist guest blogs with Diabetics - Blight of GPs; Milk Cows of Pharmacists, explaining why people with diabetes should engage their pharmacists. (He gets a blue ribbon for including a farm animal in the post title.) And a wry, trans-continental laugh for his take-away word: Pharma-conomics. Dr. Wes offers a one-word take-away to describe a mixed blessing: patient-provider e-mail. And he articulates both "added value" and "be careful" features of this mode in The Inefficiency of Medical E-Mail.

Jessica Otte explains how hard it is sleep while completing an obstetrical rotation in No electric sheep for me: Sleep is fragmented. Medical residents and how much sleep they get impacts the efficiency of individual physicians and the system that depends upon them. Her word is delusion. (I think it's meant to describe her current sleep-impaired state. But the word may also describe conventional wisdom that allowed residents' hours to remain relatively unchecked in the latter part of the 20th century.)

Over at the Healthcare Business Blog, David Williams says Atul Gawande is too optimistic about healthcare cost control when he advances the idea that the future of healthcare reform may lie in the county extension office. Williams is serious: his take-away word is pessimism. Marya Zilberberg calls out Gawande for another reason: shortsightedness. It's explained in her post Can US agriculture reform inform the healthcare debate? She offers thoughtfulness as her word.

Joseph Kim's one word is "leaving," a topic that inspired his post, Should You Leave Clinical Medicine? Finally, Jolie Bookspan offers appreciation at this time of year, with some special "academy" awards.

Correction to information for the next edition of Grand Rounds! It will be hosted next week, 12/22 by Nancy Brown of Teen Health 411. Nancy will accept submissions (to brownn at pamfri dot org) until Sunday, 12/20/09 at midnight. The theme is "coming together."

Note: The descriptors of the IOM's Six Dimensions of Care are reproduced from pages 5 & 6 of the Executive Summary, Crossing the Quality Chasm.

In keeping with Charlotte's knack for saying what she meant and meaning what she said succinctly, I've categorized this week's submissions using six words that describe quality healthcare. (They're borrowed--in ways I suspect would make Templeton the Rat proud--from the Institute of Medicine's report Crossing the Quality Chasm.) This week participants were asked to submit one word describing the inspiration or take-away lesson for their post, and you'll find their words woven into today's Grand Rounds.

I hope you enjoy the tale. And do take the opportunity this holiday season to revisit Charlotte's Web. Better yet, share it with the next generation. As we seek solutions to the vexing issues healthcare bloggers wrote about for this edition, we'll be needing new words, spun by young people whose imaginations are ignited.

The word used by the authors of Crossing the Quality Chasm to say that patients should not be injured from care intended to help them.

Last week The Blog of the Interdisciplinary Nursing Quality Research Initiative completed an ambitious commemorative series marking the 10th anniversary of To Err is Human. Since Florence dot com is, first and foremost, a real-time patient safety primer, I'm going to carefully letter my chosen word here: LEARN. And tell you to click on this link to access INQRI's lovely collection of stories, recollections, and sage advice.

Care does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic means.

Dr. Rich gets to the meat of the matter in Let Us Shun The Obese this Holiday Season. Dr. Rich's heart of darkness post (key word: demonization) could have fit nicely in many dimensions of care, patient-centered and effective sprung to mind. But his astute observation that obesity is often rooted in genetics makes it fit best here.

In The Users' Guide to the Health Reform Galaxy, Bruce Siegel stays on message with his word: equity. But read this post to learn why an insider believes minority groups could lose ground if health reform is not "done right." Louise from the Colorado Health Insurance Insider says the word is flaws and writes Why Health Care Reform is Important.

Care based on scientific knowledge should be provided to all who could benefit and not provided to those not likely to benefit (avoiding underuse and overuse, respectively).

Amy Romano, CNM gets a blue ribbon in this category for maximin, a word I didn't know and one that would surely delight Charlotte. Amy wisely included a vintage PubMed link explaining her word, and she articulates her position in What SUVs Can Teach Us About Maternity Care. Paul Auerbach discusses The Canadian C-Spine Rule, with a take-away word of algorithm. Allergy Notes offers up "allergy" as an index word for the post describing the difference between food sensitization and food allergy.

Rounding out this dimension of quality healthcare are those who prompt us to pay attention to the quality and accessibility of high end data. Eve Harris offers transparency as the take-away lesson in Asking Dr. Science. Walter Jessen at Medpedia, an innovative 2.0 health information community, uses "reliable" to describe Medpedia Now Includes News & Analysis, Alerts, Q&A. And over at Clinical Cases and Images - Blog, we're reminded that it's also helpful to think. And rewarded with a thoughtful post, Medical Textbooks and Atlases Searchable on Google Books.

Care is provided in ways that are respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values. It ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions.

Laurie Edwards says the relativity factor is confounding when people with chronic diseases go about Learning to be a Primary Care Patient. Amy Tenderich winds up in the middle here, too, a welcome place according to her Wayback Wednesday post Oh, Glorious Middle. And Rachel's simply titled post is For Now. But the word she sent along, patience, may say even more about what patient-centered care really entails.

Jacqueline at Laika's MedLibLog captures the arachnoid spirit, giving her post a one word title: empathy. The post shows how much we long for care that considers more about who we are than our "chief complaint" often reveals. If Jacqueline had been in the mood to spin longer, she could have called this post, "What comes around, goes around!"

Developmentally appropriate care may mean calling on the healing power of friendship, something Nancy Brown points out in Helping Friends Who are Stressed and Depressed. In another part of the village, Barbara Kivowitz cautions that assumptions are not always helpful in Seven Myths about Couples and Illness. And Will Meek says the word is forgiveness and writes about it in How to Forgive.

One of the things I like best about the IOM's six dimensions of care is this: stakeholders don't always wind up tangled in their own little bitty egg sacs. Lock Up Doc offers the word transparency to explain her position on Should Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder Be Told Their Diagnosis? (It's a stance that also earns her a place in the coveted "patient-centered" category.) Curiosity earns The Happy Hospitalist a place here, too. (And his post Gynecological Exams: Best Done By Male or Female Gynecologists earns another label: funny.)

Dr Charles gives a nod to resilience in his post Hypochondriachal Heroism. And child psychiatrist An Ang Zhang explains something that makes healthcare delivery a challenge: Lying people. She says more in The Smartest Lie: Lord Winston; Super Doctors & The Dark Side. But At How to Cope with Pain, the word is contest! Visit for a holiday-inspired change of pace and see what's cooking! (Spoiler alert: It's not pork.)

The need to reduce waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care.

Kim, a future nursing student, writes revisiting my hospital stay. Although she sent patience along as her take-away, I've chosen to place her post here because omissions count in quality measures. Rats!

Harry Stern at InsureBlog is worrying about supply and demand, too. His post, More (Un?)Intended Consequence, projects doctor shortages and backs up rather glum predictions with data from the Association of American Medical Colleges. ACP Hospitalist echoes the concern, with a call-to-action word: need. The post is New York survey shows dire need for hospitalists, internists. I'll take this opportunity to weave in a bit of Cavatican-style cheer: mid-levels.

Avoiding waste (of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy).

At Shoot Up or Put Up, Tim's NHS pharmacist guest blogs with Diabetics - Blight of GPs; Milk Cows of Pharmacists, explaining why people with diabetes should engage their pharmacists. (He gets a blue ribbon for including a farm animal in the post title.) And a wry, trans-continental laugh for his take-away word: Pharma-conomics. Dr. Wes offers a one-word take-away to describe a mixed blessing: patient-provider e-mail. And he articulates both "added value" and "be careful" features of this mode in The Inefficiency of Medical E-Mail.

Jessica Otte explains how hard it is sleep while completing an obstetrical rotation in No electric sheep for me: Sleep is fragmented. Medical residents and how much sleep they get impacts the efficiency of individual physicians and the system that depends upon them. Her word is delusion. (I think it's meant to describe her current sleep-impaired state. But the word may also describe conventional wisdom that allowed residents' hours to remain relatively unchecked in the latter part of the 20th century.)

Over at the Healthcare Business Blog, David Williams says Atul Gawande is too optimistic about healthcare cost control when he advances the idea that the future of healthcare reform may lie in the county extension office. Williams is serious: his take-away word is pessimism. Marya Zilberberg calls out Gawande for another reason: shortsightedness. It's explained in her post Can US agriculture reform inform the healthcare debate? She offers thoughtfulness as her word.

Joseph Kim's one word is "leaving," a topic that inspired his post, Should You Leave Clinical Medicine? Finally, Jolie Bookspan offers appreciation at this time of year, with some special "academy" awards.

Correction to information for the next edition of Grand Rounds! It will be hosted next week, 12/22 by Nancy Brown of Teen Health 411. Nancy will accept submissions (to brownn at pamfri dot org) until Sunday, 12/20/09 at midnight. The theme is "coming together."

Note: The descriptors of the IOM's Six Dimensions of Care are reproduced from pages 5 & 6 of the Executive Summary, Crossing the Quality Chasm.

Labels:

Grand Rounds,

IOM's Six Dimensions of Care

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)